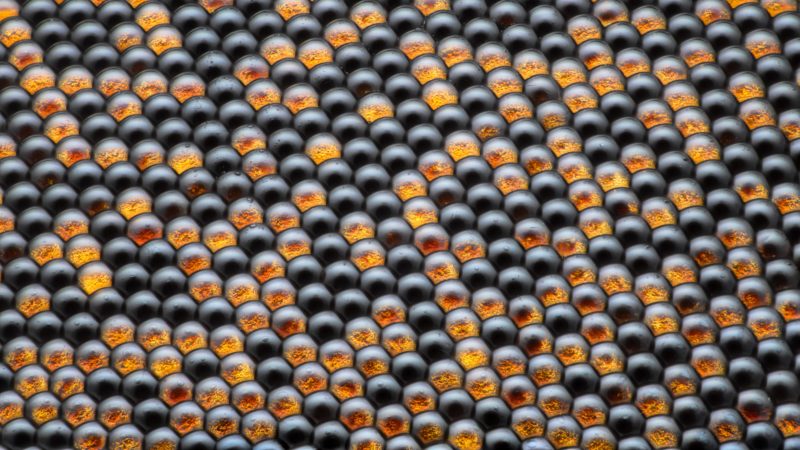

Flies look at the world in quite a different way than we do. Their eyes are made up of thousands of individual visual receptors called ommatidia, each of which is a functioning eye in itself. Therefore, a fly’s vision is comparable to a mosaic, with thousands of tiny images that converge together to represent one large visual image. The more ommatidia a compound eye contains, the clearer the image it creates.

A fly’s eyes are immobile, but their position and spherical shape give the fly an almost 360-degree view of its surroundings. Fly eyes have no pupils and cannot control how much light enters the eye or focus the images. Flies are also short-sighted — with a visible range of a few yards, and have limited color vision (for example, they don’t discern between yellow and white).

On the other hand, a fly’s vision is especially good at picking up form and movement. Because a fly can easily see motion but not necessarily what the moving object is, they are quick to flee, even if it is harmless.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Pin-It

Pin-It